“I had this episode,” says Josh Tillman. “In Philadelphia.”

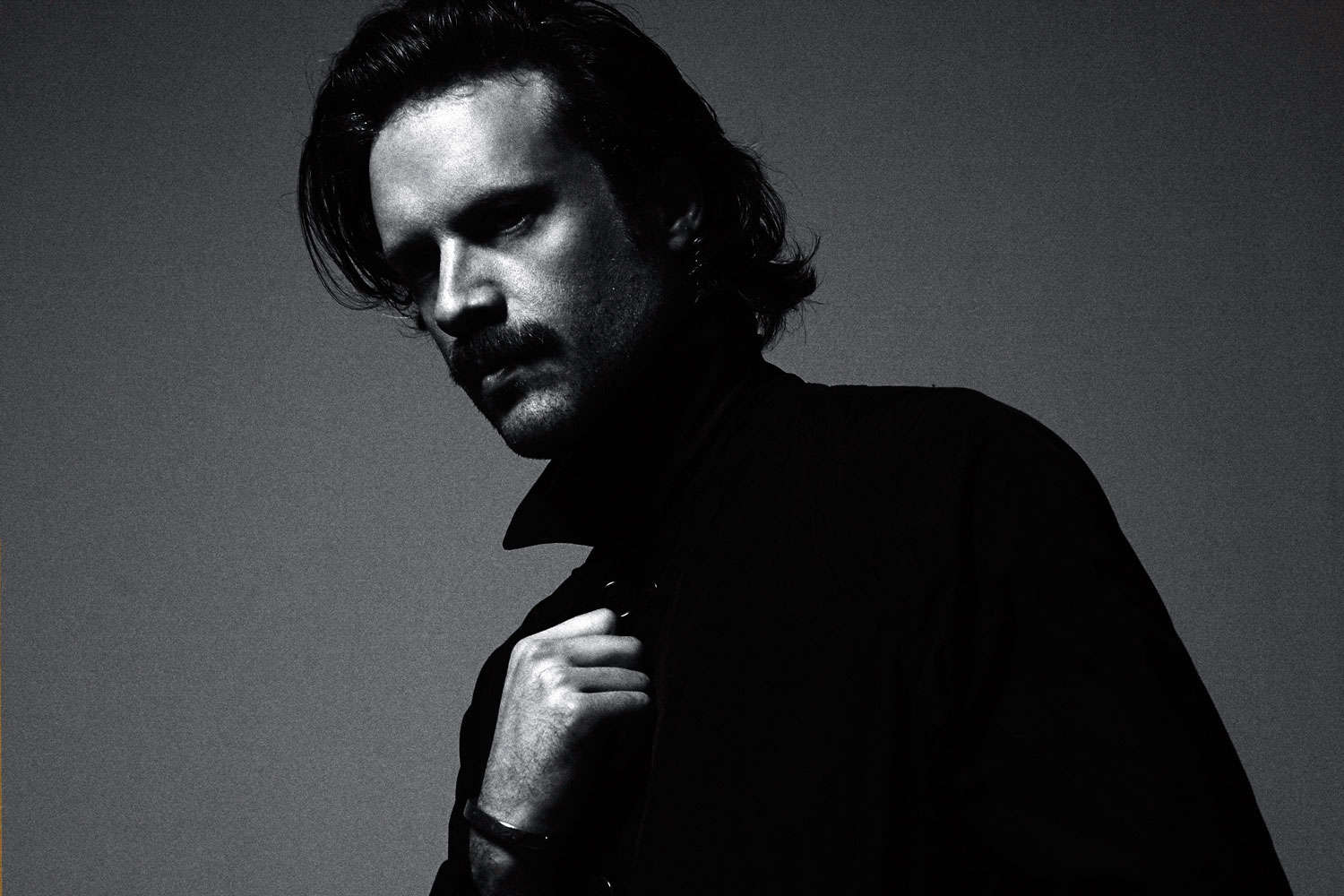

It’s a dreary, grey Saturday in Shoreditch and Josh – better known these days as his beardy, enigmatic alter-ego Father John Misty – is running the press gauntlet for his new record ‘Pure Comedy’. There’s a lot to get through. His third album is more political than his previous work, and its themes have been percolating for some time. While he started work on the album in 2015, he says that last year some of its lyrics “became very literal overnight.”

So. Philadelphia.

“It was the day after the Republican Convention, the day after Trump got the nomination,” he says. “I was horrified by that, and also horrified by the sneering, glib complacency I saw in my peers. I just thought, we’re fucked. If this is the way we react to things like this, then we’re fucked. Because what’s much worse than this? This is just about as bad and as tragically stupid of a thing as I can imagine happening. And we’re responding with more jokes.”

He is, of course, describing the lead up to his appearance at New Jersey’s XPoNential Music Festival. He still seems baffled by the events of that week, and frustrated by many people’s refusal to take Donald Trump seriously.

[sc name=”pull” text=”I just thought, we’re fucked.”]

“When I got to this festival, it was like this thing had happened and nothing had changed. People were sitting in lawn chairs drinking wine coolers and watching folk-rock. It was like-” He makes a resigned face and turns his palms out towards the ceiling, indicating the invisible masses. “- this is the left.”

When he got onstage, Josh didn’t play his set. Instead, he made a speech about the evils of Trump, half-performed two songs, and walked off. The backlash was harsh, but half a year down the line and the decision still makes sense to him.

“If this is not enough of a reason to disrupt the regularly scheduled programming, then I don’t know what is,” he says.

For a lot of people, that moment saw Father John Misty become a parody of himself. Josh Tillman has made a career from his sense of humour, entwining it with genuine songwriting ability and borderline obscene hip shaking to create a persona that is at once startlingly observant and frequently absurd. Father John Misty is enigmatic almost to a fault. Which makes it difficult to make a serious point, sometimes. Josh Tillman: the boy who cried satire.

Since Trump’s election, the writers of South Park (of all people) have suggested that in the reality where a Wotsit-tanned former reality show host can rule the most powerful nation in the Western world, we are finally beyond satire. Josh has set up an entire persona around irony, more or less, so you’d think the absurd pitch reality has taken would rain on the Father John Misty parade. But he seems at peace with it.

“I mean, I think that satire is a luxury in a sane world, you know?” he considers. “But it is very strange. I think that satire was imbued with a potential for social change in the Bush era, and we’re seeing that it does not have the world-changing properties that certain middle-class liberals would have liked. It makes me think of ‘the revolution won’t be televised’. It’s not gonna happen that way. But I don’t think anyone thought that something quite this radically stupid was possible.”

“There was a time that when people were repulsed by something, it meant that they didn’t want to see it. Now, when you put something that’s horrible or scary on TV people want to see more and more because we’ve come to – tragically- view those horrible things as having entertainment value. Because we’ve just become numb and sort of desensitised. People are waking up going-” he leans over the table, mimicking the mania of someone who’s rolled out of bed to stare into the pale glow of a computer screen – “Oh god I wonder what terrible thing Donald Trump said or did last night, I can’t wait to see. I’m going to eat my carrot muffin and see what horrible thing daddy said yesterday.”

If the western entertainment machine is part of the problem, then as an artist and performer where does Father John Misty fit in?

“Well, I’ll say this – if I had made an album about heartbreak and recreational drug use, I’m not sure I would be able to go out and perform. I don’t think I could bring myself to do it. But the fact that I have an album that does directly address these issues, I feel like I can,” he says.

[sc name=”pull” text=”I don’t think anyone thought that something quite this radically stupid was possible.”]

‘Pure Comedy’ is different to his other records. On 2015’s ‘I Love You, Honeybear’, ‘The Ideal Husband’ – a tongue-in-cheek song about wedding (and possibly bedding) Julian Assange – was about as political as Josh got. ‘Pure Comedy’, on the other hand, goes deeper into Serious Grown-Up territory. Lead single ‘Two Wildly Different Perspectives’ has seen Josh compared to Elton John, thanks to its gentle piano melody and ‘Your Song’ style vocal. Set it next to everything else he has released as Father John Misty and the instinct is to look for the joke. But it never comes. The track’s closing lines are “and everyone ends up with less, on both sides”. A simple conclusion, sure, but you wouldn’t have heard it from the Father John Misty of ‘Fear Fun’ or ‘I Love You, Honeybear’. He thinks now’s the time.

“I think artists are due up for a re-evaluation,” he says. “That’s part of the communal human experience, every once in a while we have to make big reassessments. What do we want out of music? I remember in 2008 there was this flood of indie rock that was sort of about nothing. And the culture was saying ‘there’s something magical that happens when five white men get together and play acoustic instruments’. I don’t think the culture has the same patience for that anymore, ten years later. I don’t think anyone feels that. That’s a re-evaluation.”

Bold words from a man who declared his performance on BBC 6music “the whitest, most acoustic thing you’ve ever seen,” but it’s true that on ‘Pure Comedy’, Josh is getting real.

Still, the sarcastic shaman hasn’t ditched his old MO entirely. The record is still brimming with his black humour, with tracks like ‘Ballad of the Dying Man’ and ‘Things It Would Have Been Helpful to Know Before the Revolution’ poking holes in our capitalist habits. ‘Pure Comedy’ is Josh trying to make a serious point, but it’s wreathed in the same wry amusement that’s tinged everything he’s done as Father John Misty.

He doesn’t think the humour cheapens the politics, but he’s wary of crossing too far into that territory.

“There’s a distinction between art and culture and entertainment,” he points out. “Culture is how we determine what our values are. And I do think that this album is my bid at trying to articulate what our values are. Culture can be entertaining, but something that’s purely entertainment is just a narcotic.”

Josh is well aware, though, that no matter how well intentioned he is there are people who have no interest in his version of our cultural values.

“Since some of the songs have come out, plenty of people have said, ‘I don’t think anyone cares what fucking Father John Misty has to say.’ There are people who completely despise me and think that I’m the last person in the world who should be a mouthpiece for how to move forward,” He says. “They don’t want it to be me. I think the response to this album is going to be really polarised.”

Since he sat down today he’s moved back and forth between tiredness and animation, but now he seems properly bummed, if in an unsurprised sort of way.

“It’s depressing. It’s disheartening. But there’s no way to go but further into the fray. If interviewers are asking me I’m not going to say, ‘Well I don’t think I’m the person to be talking about this’. I can’t do that either. I can’t hide,” he shrugs.

“I think what turns a lot of people off about my music is that a lot of the questions I’m addressing are clichés, like ‘What is love?’ or ‘Why are we here?’ ‘What does it all mean?’ But that’s what all my favourite artists are asking, whether it’s Terrence Malick or David Lynch. For a certain type of artist you’re crippled with self-awareness, so when you go ‘I want to make a song about why we’re here,’ then you go -” he drops his head into his hands, violently cringing at himself, “‘Oh god did I really just think that?’ But you can’t get it out of your head, so you do your damndest to do it justice. There ends up being self-awareness in the work, and awareness of the awareness. In my song ‘Leaving LA’, I’m making a meta-commentary on the song as part of the song. I think that strikes a lot of people as pretentious, but it’s just my way of dealing with how cliché the questions that I’m asking are.”

If Josh is asking clichéd questions, it’s only because he’s unsatisfied with the clichéd answers he’s been given. He was raised an Evangelical Christian but has clearly strayed from the flock, dabbling in psychedelics and philosophy to try to find the solution himself. He’s getting closer.

“Life is just narrative metadata in aggregate. Modern man’s solutions for the human riddle, I think are pretty counterfeit. We can do better,” he says. “We can do better than that. And the answers I don’t think are all that sophisticated. I think our vanity wants to think that the answers are really complex, and I don’t think that they are. I think we have everything we need. You know? How could we need much more than this?”

One of the ‘solutions’ that he appears to find particularly counterfeit is consumer culture. He seems preoccupied with capitalism these days, but then maybe he always has been – he’s sung about global markets crashing before on I Love You, Honeybear. Pure Comedy takes things a step further, as ‘Things It Would Have Been Helpful to Know Before the Revolution’ sees us return to living off the land. Our social lives are ruined, but it’s okay, because as Josh sings “there are some visionaries among us developing some products to aid us in our struggle to survive.”

He thinks people are self-sabotaging like that. They’ve got that classic Fight Club “the things you own end up owning you” problem.

“That’s the irony of human beings. The things that make us so unique – our creativity, our ambition, our insatiable appetite for progress – the things that make us so incredible make us destructive,” he says. “The difference between those two is consciousness. Consciousness enables us to use our talents and inspiration for the good of other people. Money doesn’t have a conscience. Capitalism doesn’t have a conscience. It makes the world binary. It turns the world into supply and demand. It kind of makes us monstrous in a way. It kind of makes us deny our consciousness.”

[sc name=”pull” text=”Money doesn’t have a conscience. Capitalism doesn’t have a conscience.”]

The answer, he says, is to hold onto and care for each other. Compassion. Unity.

“People will look at the title of this album and go ‘that is a flippant, cruel, narrow-minded perspective on who we are and our condition.’ But I think that there’s compassion in that. We’re all in this absurd state of affairs together, and we can only move forward if we recognise the absurdity and laugh. The end of the album is like, what is there to fear? We’re so insignificant. And it’s statistically a miracle that we’re here. So why be so serious? Who are we kidding? Come on!” He laughs, incredulous now, and it’s infectious.

“I think that’s going to be the biggest misunderstanding with the album. When I say, ‘Just random matter suspended in the dark’, that’s not despair. It’s just saying let’s have some perspective.”

In himself, at least, Josh seems to have found a perspective he can live with.

“You get to some point where you realise that fundamental questions have fundamental answers. I like the fewest moving parts. I’m not impressed with a lot of answers that this culture offers. They just don’t sit right with me. I think that is the core of existentialism, is that culture and society or religion or philosophy have all failed to answer these questions.” He decides. “And you have to answer them yourself.”

Father John Misty’s album ‘Pure Comedy’ is out now.