The trouble with real life is that there’s no danger music,” quips Jim Carrey as he climbs a satellite dish at the climax of ‘The Cable Guy’. Yeah, the film’s pretty shitty but a young Matt Healy, perhaps six or seven years old, heard this and it resonated. Suddenly everything made sense; life would be better with musical accompaniment.

“When I was younger, music was a portal,” he explains. That line from The Cable Guy was the first time that idea had occurred to him. “I soundtracked my life. My wish was that in all of those moments where I felt certain things, they were viewed with a musical memory. That’s why The 1975 became so cinematic.” Documenting his life in song, “you can see the inspiration from John Hughes and the cinematic portrayal of youth and that apocalyptic feeling of being young,” across both albums. “That all comes from me wanting to live my life soundtracked.”

Based in the everyday grime of reality but treasured like it’s the only thing that’s ever mattered, The 1975 tackle it all. Singing about loss, acceptance and a devil-may-care abandon, they capture very real moments. For Matty, the band has always sung ‘The Ballad Of Me And My Brain’. It just so happens that with ‘I Like It When You Sleep, For You Are So Beautiful Yet So Unaware Of It’, he’s written a soundtrack for an entire generation. Not that he’s buying into that idea just yet.

[sc name=”pull” text=”Get up. Go and fucking do it.” ]

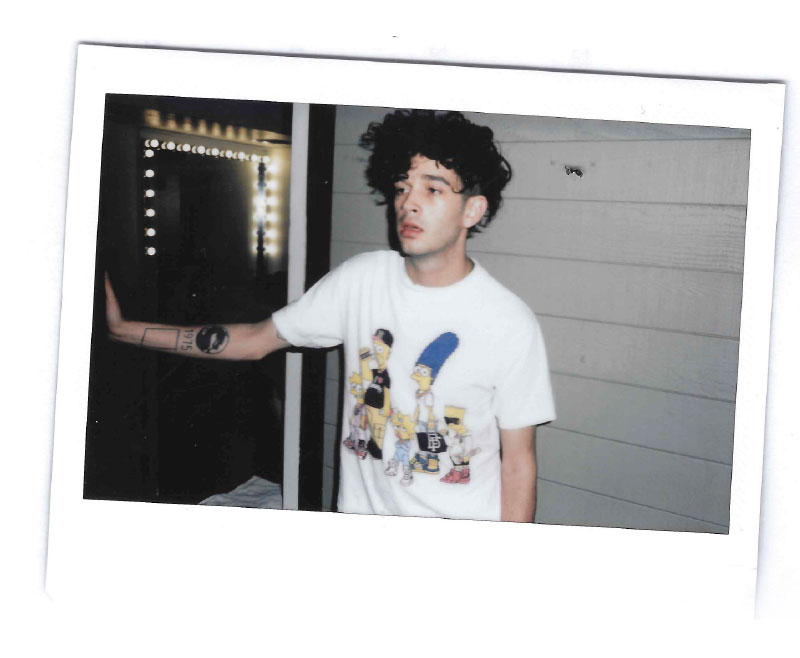

In a Toronto hotel, Matty speaks a million words a minute. He’s just woken up, and he talks a lot in mornings. Ideas are born and die over the course of a sentence; there’s a temptation to make facetious jokes about drugs and there’s a constant worry about misrepresenting himself. He uses Marc Bolan as his yardstick for glam rock star excess. He quotes Thom Yorke, Noel Gallagher, Ricky Gervais and he hears what he’s saying in real time. Halfway through a sentence, he stops and laughs: “Don’t write me up to sound pretentious or over-inflated,” because he knows what’s coming next. He avoids the comment section but will read interviews with himself because he’s interested in how his words translate. He’s a writer after all. Every detail of a story is important, and despite the gruelling year The 1975 have had, he never complains. That’s an “element of being English”: “Get over yourself. What would you rather be doing, washing dishes at the fucking Plough and Flail in Alderley Edge? Get up. Go and fucking do it.”

This year, The 1975 have indeed gone and fucking done it. They’ve had a couple of big years behind them, but 2016 has been bigger still. They’ve gone from a weird cult band with a Number One album to a weird not-really-that-cult-anymore band with two Number One albums. With their self-titled debut, people struggled to place them in the larger musical landscape, but with the follow-up, they’ve got a space all of their own. Matty and the boys (George Daniel, Adam Hann and Ross Macdonald) haven’t had much time for that, though. After all, it’s hard to be objective; they’ve become immersed in their world.

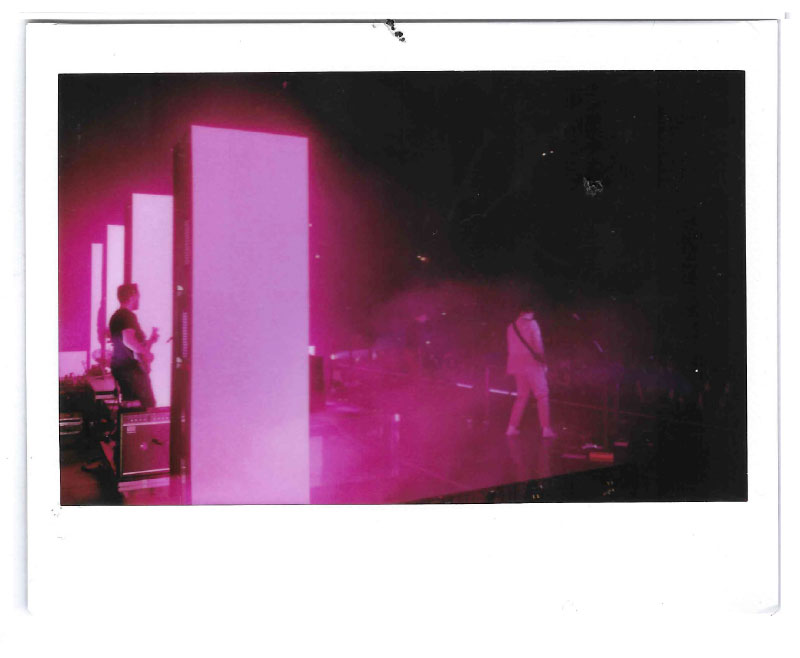

“Touring is almost the foundation for my life now,” explains Matty. “I get to go out most nights and see thousands of people who want to come and see us, so that’s incredibly humbling, rewarding and a big change from the majority of the time I’ve spent in this band.”

“Touring is almost the foundation for my life now,” explains Matty. “I get to go out most nights and see thousands of people who want to come and see us, so that’s incredibly humbling, rewarding and a big change from the majority of the time I’ve spent in this band.”

Formed in 2002, The 1975 have spent most of their existence being ignored. They’ve struggled to sell ten tickets in Manchester and “couldn’t get fucking arrested” until they were 24. “All the labels came down to meet us. We were a known band in the industry, but nobody wanted to sign us.” Apparently, they were just too eclectic. It shaped who and how they are today. “We got used to being this insular band that just operated in and around Manchester and Cheshire. There was a lot of safety in that. All those songs that are on the first album were written in that time, and when it came out and became so successful, especially amongst so many young people, I was like, ‘Woah, woah, woah, woah! That’s not all I’ve got to say.’ The whole thing just happened so fast. For me, that album was quite confusing, so I don’t know what it was like for other people.

“In my mind, that record is tied to the idea of becoming known. Not a desire to be famous but wanting people to know who my band is. There’s an element of ego involved in that, an element of jostling for position and for people to take you seriously or think you’re cool.”

With the release of ‘The 1975’, people started listening. And looking. The band had a position. They were known, and they were cool. Suddenly, the insular group had to deal with the world as a whole. When it came to making album two, they had to pretend it wasn’t there. “We had to not care to make the album that we did in the end. We made a really, really honest record; a record we wanted to make, and for us, it was really uncompromising. I know we make pop music but we just wanted to make a really free record and that was the record that, in turn, went on to be our most commercially successful and globally accepted. My only intention was to show what we do. To be these ambassadors for this generation of millennials who consume music in a certain type of way. It’s been amazing for us. When you stop trying so hard, it kinda works.”

With the release of ‘The 1975’, people started listening. And looking. The band had a position. They were known, and they were cool. Suddenly, the insular group had to deal with the world as a whole. When it came to making album two, they had to pretend it wasn’t there. “We had to not care to make the album that we did in the end. We made a really, really honest record; a record we wanted to make, and for us, it was really uncompromising. I know we make pop music but we just wanted to make a really free record and that was the record that, in turn, went on to be our most commercially successful and globally accepted. My only intention was to show what we do. To be these ambassadors for this generation of millennials who consume music in a certain type of way. It’s been amazing for us. When you stop trying so hard, it kinda works.”

[sc name=”pull” text=”When you stop trying so hard, it kinda works.” ]

Looking back at the creation of ‘I Like It When You Sleep…’, Matty has convinced himself that “at no point did I think about the critics or being objectified or worried. I think I’ve idealised that album recording process as me just creatively gallivanting around the studio, doing whatever I wanted. I’d convinced myself I didn’t really care. ‘I don’t give a fuck about awards; I just want to make records. I’m going to be a pop outsider, don’t include me in anything. Oh, Mercury nomination, that does feel quite nice.’ Maybe I do care about these things.” Not that the reaction has been that much of a surprise. “I live these records. I do a show, go to a hotel room, work on music and document my psyche. But it makes me think, if somebody does put as much heart into what they do as we did with that record, then it should be commercially successful. So, I have been a bit surprised, but I have been a bit, ‘Yeah, too fucking right’, too. I worked really hard and I can tell that song connects with people. What I’ve done now is start to accept the fact that The 1975 is more accepted in different worlds.”

‘I Like It When You Sleep…’ is – in its own way – a bizarre album. It covers so much ground and deals in everything from acceptance to loss, ranging from delicate minimalism to commanding blow-out. As big as the record reaches, though, The 1975 never use that scale to hide or distract. The band deals in the blunt truth.

“It’s interesting when you talk about hiding behind something because I would rather lacerate the pomposity in front of you. As much as there’s that ‘Love Me’ rock star, post-Marc Bolan, ridiculous cliché part of my performance, there’s an insecurity there. When I perform live, I’m never thinking I’m actually Mick Jagger. There’s a fragility there and I think it’s the same in the record. When things get too much for me, in regards to it feeling faux or slightly contrived, then I have to reference it or change it. I think the problem is the self-awareness of it. You can’t be a proper rock star anymore because everybody else has everyone’s number. Everybody knows being cool is just referencing stuff. It was way harder to be cool ten or twenty years ago because you had to have seen that film or been to that bookshop or been at that show, whereas now everybody’s got a computer in their pockets so you can reference things at a million miles an hour. Now my generation’s first response when they see something cool is to be suspicious of that. They think that’s probably not real, or they’ve learnt that from somewhere else, and that’s the way that people act now. There’s an element of that in my identity, so there’s an element of that in my music. It’s calling myself out before people get a chance to do it. I even do it musically, the number of times I call myself a cliché, it’s all part of the way that I hope I become relatable.”

“It’s interesting when you talk about hiding behind something because I would rather lacerate the pomposity in front of you. As much as there’s that ‘Love Me’ rock star, post-Marc Bolan, ridiculous cliché part of my performance, there’s an insecurity there. When I perform live, I’m never thinking I’m actually Mick Jagger. There’s a fragility there and I think it’s the same in the record. When things get too much for me, in regards to it feeling faux or slightly contrived, then I have to reference it or change it. I think the problem is the self-awareness of it. You can’t be a proper rock star anymore because everybody else has everyone’s number. Everybody knows being cool is just referencing stuff. It was way harder to be cool ten or twenty years ago because you had to have seen that film or been to that bookshop or been at that show, whereas now everybody’s got a computer in their pockets so you can reference things at a million miles an hour. Now my generation’s first response when they see something cool is to be suspicious of that. They think that’s probably not real, or they’ve learnt that from somewhere else, and that’s the way that people act now. There’s an element of that in my identity, so there’s an element of that in my music. It’s calling myself out before people get a chance to do it. I even do it musically, the number of times I call myself a cliché, it’s all part of the way that I hope I become relatable.”

Whichever way you look at it, The 1975 connect. Self-aware and tuned in, everything they say feels real. The more the band have opened up, the more the world has taken to them. “You know what I hate, though,” asks Matty, answering instantly: “People who say, ‘Oh, I just say it like it is’. Yeah but that doesn’t mean you’re not a dickhead. It doesn’t stop you from just saying things that make you a dick. But what I am very aware of is when people are really honest, respectful and they’re frank and they say how they’re feeling, even if talking about part of themselves that’s quite distasteful, it can be quite endearing having someone saying it how it is. Loads of people come up and talk to me about ‘Nana’. Of course, if you write a song about the death of a loved one, it’s going to connect with loads of people, ‘cause people die. The specific thing that people talk to me about with that song is its lack of metaphor because death is the ultimate context of metaphor. I’m not that good at metaphor and when I had to write about it, there’s a line in it that goes ‘I don’t like it now that you’re dead’. When there are things that make me feel blunt, it provokes me to be blunt. And I think that’s what we’re talking about in terms of that openness; there’s something about me being frank about something that maybe you’d be less frank about.”

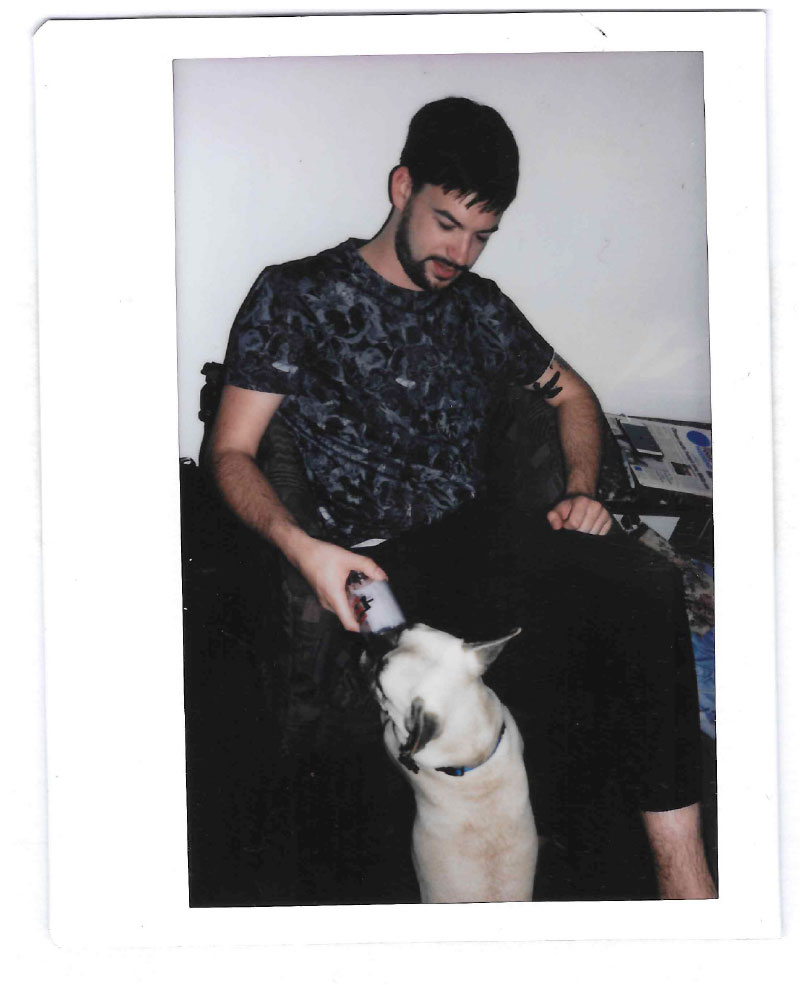

Matty has yet to push that frankness too far. He’s yet to draw a line because he doesn’t need to, “because I’ve got the boys. We’re obviously so close and we’ve been together for so long, everything I write has to be true because one of them, at least, is with me all day. I can’t make up some narrative about some girl I was in love with. If I went too far, one of them would say, ‘Listen, man, you don’t need to be putting that shit out there. That’s too heavy. That’s just indulgent’. There’s a time for it to be harrowing – I adore Antony and The Johnsons – but music is still an escape for people and I only want to write about stuff that’s cathartic for me but also helpful for other people. I don’t want to cross into the aggressively indulgent. There’s no time for that with me.”

[sc name=”pull” text=”I really do live these records” ]

As intricate, winding and horizon-stretching as ‘I Like It When You Sleep…’ is, the line in ‘Paris’ “Hey kids, we’re all just the same. What a shame” sums it all up. “You can’t be objective to what your favourite lyric is but in regards to when we do it live, when I hear it, when I remember writing it, when I remember the feeling, it sums up the album now. When I wrote that line and I had that song ‘Paris’, I felt like I knew what the album was. That inspired ‘Loving Someone’ which inspired the whole glue of the knowledge of us all being a witness to this madness. I know in The 1975 we use the paradigm of my life to look at the world and talk about it, but most young people’s desire is for everybody to be caramel and queer. I think that line sums up the whole record. Our shows are so multi-everything. When you’ve got white kids, Sikh kids, black kids, all these kids at your show all singing that line and it resonating in such a literal way, it’s hard to get away from.“

Despite the crowds growing, it just makes Matty feel way more a part of it. People spend a lot of time asking him how crowds from different countries compare to one another but that’s a tricky one to answer, ‘cause touring the world has taught him something else. “You realise that it’s not the differences you notice, it’s the consistencies. Whether that’s unique to The 1975 shows, I’m not sure but I’m telling you, we play to the same group of people, the same group of kids every night. Bangladesh, Alaska, Hackney. It’s the same type of people and sure, their hair might be a different colour over here or they might look slightly different over there. The thing is, people seem to notice the differences but for me, you have to search for the differences. It’s the similarities that are blindingly obvious. It’s why it confuses me with the culture we’re in. The internet has opened up the doors and exposed everybody to everybody, shown everybody how different everybody is from one another, and that’s created this hardening of position and people becoming scared of one another. There’s this polarity of stuff, so it’s interesting at The 1975 shows because we don’t really have that as much, it’s just this weird community.”

Despite the crowds growing, it just makes Matty feel way more a part of it. People spend a lot of time asking him how crowds from different countries compare to one another but that’s a tricky one to answer, ‘cause touring the world has taught him something else. “You realise that it’s not the differences you notice, it’s the consistencies. Whether that’s unique to The 1975 shows, I’m not sure but I’m telling you, we play to the same group of people, the same group of kids every night. Bangladesh, Alaska, Hackney. It’s the same type of people and sure, their hair might be a different colour over here or they might look slightly different over there. The thing is, people seem to notice the differences but for me, you have to search for the differences. It’s the similarities that are blindingly obvious. It’s why it confuses me with the culture we’re in. The internet has opened up the doors and exposed everybody to everybody, shown everybody how different everybody is from one another, and that’s created this hardening of position and people becoming scared of one another. There’s this polarity of stuff, so it’s interesting at The 1975 shows because we don’t really have that as much, it’s just this weird community.”

That’s why The 1975 are soundtracking a generation: they take being an outsider and champion it. They shine a spotlight on what makes them different and people can see themselves in it. “There’s a cultish element to this band,” starts Matty. “It’s just grown. It wasn’t like we had a hardcore group of fans, then we had one hit single and everybody’s mum started showing up to The O2 to see us. It is massive now but it’s grown with every single kid. When we used to play shows to 300 people, 100 would wait behind to meet us and there’d be kids with The 1975 tattoos. There was this intensity early on that just seems to have spread and spread. With these kids, they just live for The 1975 and the thing they all tell me about is how they all met, or are all friends because of this and that’s the community that interests me. It all gets like Skynet, Terminator shit. It’s an idea that starts in your bedroom, and it’s never got any bigger than that. You’ve got people saying that idea is starting to define a generation; there’s no way to be objective about that unless you come across as insanely pretentious or you buy into your own bullshit, and I can’t do that. I’ve just got to keep being me. I need to keep the purity of the pursuit, the pursuit of excellence for my own self.”

People have found a voice within The 1975. That comes with pressure to speak up, to become a spokesperson. It’s one of the things he’s struggled with, “but I’ve realised that I don’t have much control over myself when I’m in an interview, I’m such an impulsive person, and I’m quite a genuine person, so I fuck up quite a bit. I get worried about misrepresenting myself and therefore being an idiot but I don’t feel personally responsible. On this album, what I wanted to do was use my platform to make people as passionate and conscientious as possible, but at the most times, do that through my music. It’s way more powerful to have that line in ‘Paris’ or songs like ‘Loving Someone’ as opposed to a speech every day on Twitter. I’ve got opinions – the amount I could have spoken about American politics – but I’d rather try and create three minutes of something that’ll last forever and really means something as opposed to something that doesn’t mean as much that’ll last for just as long. I try and keep it in the music. There are charities I’m aligned with like the British Humanist Association. There are certain things I stand against; I’m very anti-faith schools and I’m all about the disruption of religious rule. There are lots of things I’ll vocalise, and I’ll talk about if asked but I don’t want to be…,” he goes quiet. “I get very, very, very scared of being known for anything apart from The 1975. I get anxious for being known for anything more than my music. I just think it’s way better for people if they’re persuaded through an art form instead of someone just waxing lyrical about something.”

Despite his fear of being misrepresented, Matty puts a lot of faith in his audience. There’s a subtle art to his delivery. ‘I Like It When You Sleep…’ covers everything from heartfelt sincerity to tongue-in-cheek jokes. There’s no chance of being spoon-fed with The 1975. “I give people the benefit of the doubt because I expect to be given it as well. I expect to be able to say things and have people say ‘he’s joking’ and if I don’t do that with other people, then I’m a dick. I want a strict door policy on my band. I don’t want every fucking idiot getting in. I love that saying, ‘If you’re offended, it doesn’t mean you’re right’. I don’t need to justify or apologise or ask permission to talk about anything, but I expect my fans to give me the benefit of the doubt because there’s so much of my personality and morality and what I stand for in our music. If I do say something that’s slightly sassy or a little bit controversial, people will assume that there’s nothing to be offended by. People aren’t fucking stupid, though.”

Take the faux-arrogance of ‘Love Me’, playing up to stereotypes and turning them on their head with a tongue-in-cheek smirk. It walks a line between smart and silly without a disclaimer. The track is “just taking the piss out of myself, basically. Love me, fine, if I’m the one you’ve decided to love then let’s do it. There was enough of a foundation of me being emo and weird and insecure for people to know that between albums I hadn’t become Marc Bolan. ‘Oh my God, he‘s actually turned into *that* guy. I wish I was like that, fuck me, that’d be awesome. I’d love to be that person but unfortunately not. The 1975 is me and my brain. It is a complete paradigm; I suppose that would be the word. It’s a whole vocabulary.”

Take the faux-arrogance of ‘Love Me’, playing up to stereotypes and turning them on their head with a tongue-in-cheek smirk. It walks a line between smart and silly without a disclaimer. The track is “just taking the piss out of myself, basically. Love me, fine, if I’m the one you’ve decided to love then let’s do it. There was enough of a foundation of me being emo and weird and insecure for people to know that between albums I hadn’t become Marc Bolan. ‘Oh my God, he‘s actually turned into *that* guy. I wish I was like that, fuck me, that’d be awesome. I’d love to be that person but unfortunately not. The 1975 is me and my brain. It is a complete paradigm; I suppose that would be the word. It’s a whole vocabulary.”

He doesn’t have synaesthesia but “as soon as we’re working on a song, I know what colour it is. Not in a pretentious, wanky way but there’s an element to it. I knew how I wanted to light the video for ‘Somebody Else’ and how I wanted to light the video for ‘The Sound’. I have quite a visual brain so when I’m writing lyrics, I suppose I’m writing a little video as well. I’m visualising it. I’ll have a book where the song and the lyrics and the video are all on the same page. I write it all at one time, and then we finish at once. It’s the same with the artwork. We had the album cover [for ‘I Like It When You Sleep…’] before we even started writing. That album cover was up in the studio, so we knew what we were working towards because I already knew that was the visual identity. Those kind of things come first. The whole thing feels like a creative expression as opposed to just being the music. It’s my world and my life, and if people are going to be witness to it, then it needs to be perfect.”

‘I Like It When You Sleep…’ celebrates the moment, and the band are trying to live accordingly. “We’ve always had friends on tour with us, taking photos and filming stuff, and occasionally you’ll see a photo and think, ‘Fucking hell, that was three years ago. Look at the size of the venue, look at your beard, you look like a right cunt’. There are always moments of nostalgia that bring you back to the whole thing being a huge story.” The band reflect a lot more than they used to, “just because we’re a bit older and we wear trousers instead of jeans occasionally. The 1975 is a big thing now, so there are grown-up conversations to be had, but we try and subvert them as much as possible by doing them naked or something. It’s very much just us touring the world and having fun.”

[sc name=”pull” text=”It’s already quite a weird record. I’ve written a lot of it.” ]

The band will sit in venues and work on material for the next record but they’ll also stop and vocalise the fact they’re about to play a show to thousands of kids in Pittsburgh. “Fucking hell, that’s mental. When we did the Apollo in Manchester, I sat at the dressing room window from 10 o’clock in the morning and I watched as every single kid turned up, because I know what it’s like to go to a show there. I know what buses you have to get if you want to go from Wythenshawe or Cheadle. I know what it’s like when you come out The Apollo and your ears are ringing and you get in your dad’s car and it’s deathly silent and the indicators sound insanely loud and you’re really sweaty. The amount of history I had with The Apollo, I sat there and I really appreciated it. I really got it and I really felt ‘fucking hell, this is full circle’. We do the M.E.N. in December. I might as well have lived at the M.E.N. when I was 15 I was there so much. Those things you can’t take for granted, they shake you up.” As much as they’ve enjoyed the story so far, they’re onto the next thing.

“I think every great artist has been about evolution and progression, but the greatest artists have had that Thom Yorke quote-thing where your records become distillations of the records that preceded them. You take what’s amazing about the previous record and you distil it and you refine it and extend it and you build upon, that’s always our idea.” But as for specifics, “I don’t fucking know. I talk a million miles a minute and I’ll be writing one song and I’ll think I’ll know what the whole record is going to sound like and it completely changes. I know that it’s going to be more all over the place than the last record in regards to it being recorded in so many different places. It’s already quite a weird record. I’ve written a lot of it. It’s going to be… I don’t know. It is interesting to think I don’t know. I’ve got an idea of what I want to do visually and then it becomes a process of procrastination, figuring out exactly what I want to do.” There was talk of new The 1975 in 2017 because of a blunt tweet that said “New The 1975 – 2017.” And, “there will be something but that was me slightly pissed and being honest with myself about how impatient I am. There’s not going to be another album next year because we all know how seriously I take our albums, but I think we’ll put out a piece of music. We’ve met so many people recently along the way and we’ve met so many artists who we’re not necessarily going to be working with, but it’s been a very inspiring time for us. I just know we’ll definitely put out a single next year or an EP which will lead up to the album which I reckon will come out early summer 2018, and it’ll be really sad but it’ll change the world ‘cause it’ll be fucking sick. There’s a quote for you.”

The 1975 have connected like so few bands manage. They’re a genuine, worldwide phenomenon but you ask Matty why he thinks this is, and he’s more interested in what you think. He listens and readily admits he doesn’t fucking know. “If I knew, I’d be doing it more. If there was remotely a formula to it, I’d have done it another two times.” He pauses, before asking: “Do I have to care? Like, because I can feel like I can appreciate it without intellectualising it too much. I don’t want to review it. That’s the sort of thing you do when you come out of a relationship. Maybe when we break up, I’ll do a mind retrospective where I’ll figure everything out but right now, I’m really humble and I’m very lucky. I don’t think people realise how much we do it for ourselves. Anytime you pull a leather jacket on or go out on stage, there’s an element of showmanship there. What the 1975 really is, is me and George smoking weed in a bedroom and making records. That’s all we do. Instead of sitting there and watching a film and getting wrecked, we’d play around and make a tune on a laptop. Now, imagine sitting around and watching a film became your job. That’s fucking wicked, and that’s what’s happened with me. It’s the same thing. I’m just in Toronto and it’s a hotel room instead of my bedroom but still, why would you want to go out?

The 1975 have connected like so few bands manage. They’re a genuine, worldwide phenomenon but you ask Matty why he thinks this is, and he’s more interested in what you think. He listens and readily admits he doesn’t fucking know. “If I knew, I’d be doing it more. If there was remotely a formula to it, I’d have done it another two times.” He pauses, before asking: “Do I have to care? Like, because I can feel like I can appreciate it without intellectualising it too much. I don’t want to review it. That’s the sort of thing you do when you come out of a relationship. Maybe when we break up, I’ll do a mind retrospective where I’ll figure everything out but right now, I’m really humble and I’m very lucky. I don’t think people realise how much we do it for ourselves. Anytime you pull a leather jacket on or go out on stage, there’s an element of showmanship there. What the 1975 really is, is me and George smoking weed in a bedroom and making records. That’s all we do. Instead of sitting there and watching a film and getting wrecked, we’d play around and make a tune on a laptop. Now, imagine sitting around and watching a film became your job. That’s fucking wicked, and that’s what’s happened with me. It’s the same thing. I’m just in Toronto and it’s a hotel room instead of my bedroom but still, why would you want to go out?

“There’s a great Noel Gallagher quote in that new film that goes, ‘When I found weed and guitars, what the fuck do you want to go out for’. It was the same with George and me, once we found weed and a laptop, what’s the point? Why would you want to go out, people can come over but let this be the nucleus of our life and everything else can orbit around it. That’s been happening for ten years. I don’t need to think about it more than that; it’s my life and it’s what I do. I just want people to do what I did. Music, y’know? Awards and being part of culture that way, that’s all really nice but what really excited me is a couple arguing in their car in Cheadle, near where I’m from, while one of our songs is on and then that forever becomes part of their history. That’s the shit that excites me, when our music bleeds into humanity. That’s what I’m into and that’s because of how I write it. It’s all a cinematic version of reality. That’s what I want people to take away from it. It’s just nostalgia, innit. I want it to be nostalgia.” [sc name=”stopper” ]